Over 530 million people are suffering from diabetes, and 90% of those cases are type 2 diabetes.1 Type 2 diabetes involves both insulin resistance and decreased insulin production.1 Insulin acts as a signal for cells to remove sugar from the blood, so if cells are resistant, the sugar cannot be removed from your blood, leading to many dangerous outcomes due to high blood sugar. The lack of insulin production is due to the loss of pancreatic beta cells, which also results in high blood sugar.1 The lack of insulin production occurs in type 1 and 2 diabetes. Therefore, in today’s study, we discuss a patient with type 2 diabetes who underwent a stem cell transplant.

Three takeaways to tell your friends:

- Stem cells can be made from a patient’s cells.2

- Those stem cells can be grown into cells for clinical purposes, like pancreatic beta cells for a diabetes patient.2

- When a patient receives pancreatic beta cells grown from their reprogrammed stem cells, they can overcome their type 2 diabetes symptoms.2

First, we will discuss stem cells and then the study.

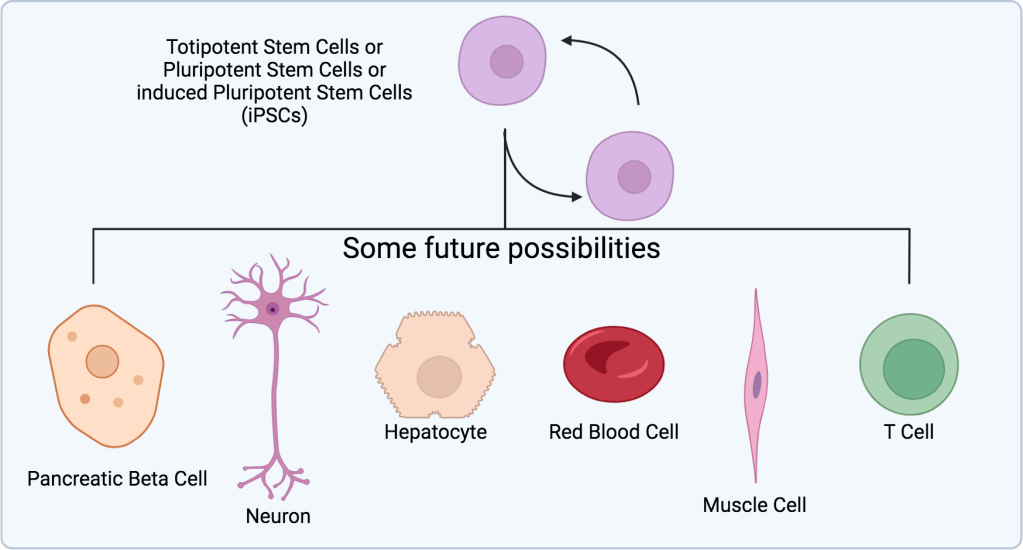

What are stem cells? Stem cells are the parents of all cells in our bodies. They can become any cell that the body needs. Need more skin cells, “done.” Need more blood cells, “on it.” Need more muscle cells, “you betcha.” Albeit, it’s way more complicated than that, but the point is that stem cells can become any cell in the human body. They also have a constant supply. They group in a bottomless reservoir where they constantly multiply, like tumor cells, but contrary to deadly tumor cells, stem cells are beneficial and essential. Stem cells are named based on which cells they can morph into. It generally boils down to this:

- Totipotent stem cells – can become any cell in the human body

- Pluripotent stem cells – can become cells of almost every tissue (e.g., muscle, blood, brain, skin)

- Multipotent stem cells – can become cells of one tissue (e.g., muscle)

For most lab work, researchers want pluripotent stem cells. This allows them to morph the stem cells into nearly any desired cell type (Figure 1). However, both pluripotent and totipotent stem cells are, typically, only found in embryos.3 To overcome this lack, scientists uncovered something pretty crazy. It’s that cells remember their past.

Imagine an older person. They want to be young again, so you show them videos of themself as a child. Suddenly, memories come flooding back to them. That’s what I’m about to explain, just in cells.

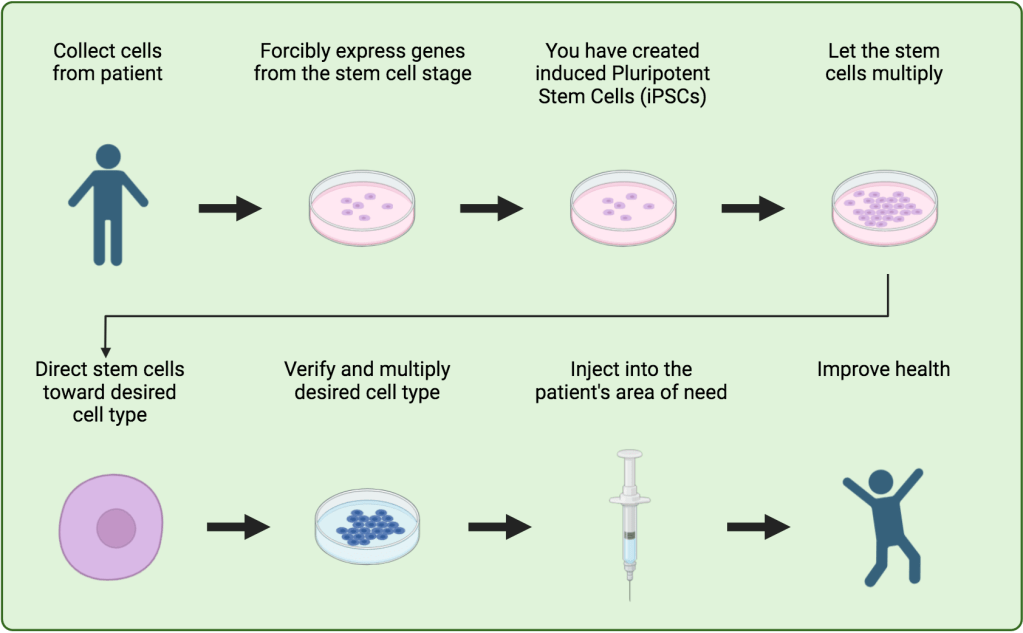

Let’s take grown-up cells (not stem cells, but cells with a purpose), like fat cells. If you take these cells and forcibly express genes from their time spent as stem cells (induce), they will reverse back into pluripotent stem cells.3 In scientific terms, you have reprogrammed fat cells into induced pluripotent stem cells or iPSCs. Now, you know the lingo.

From there, with the knowledge of how the human body develops, plus their pluripotency, we can direct them to grow into nearly any cell type (Figure 2). Just consider the possibilities. Again, they are more complex but endless:

- Genetic blood disorder, here’s more red blood cells.

- Damaged heart tissue after heart failure, here’s more cardiomyocytes.

- Liver damage, here’s some hepatocytes.

- Muscle damage, here’s some muscle cells.

- Type 2 diabetes, more pancreatic beta cells?

The best part is, after transplanting into a person, there’s no fear of them rejecting the cells as foreign material, like in an organ transplant. That’s because the cells came from that person. It’s like donating yourself a healthy kidney, but on a much smaller scale.

Now, back to today’s study, where they apply this method. As briefly mentioned, the lack of insulin production in type 2 diabetes is due to the loss of pancreatic beta cells. To replace bad pancreatic beta cells, the researchers collected blood cells from the patient to reprogram into stem cells.2 After reprogramming the cells into iPSCs, they were directed to grow into pancreatic beta cells.2 Once collected, the cells were injected into the patient’s liver.2 There, they can access circulating blood. The goal was that new cells would produce and release the insulin that the patient’s bad pancreatic beta cells had stopped releasing.2 This release would be in higher concentrations than before, which would help overcome the patient’s insulin sensitivity and curb diabetes symptoms.

The results were astounding. Following the implantation, they monitored the patient for 116 weeks.2 The patient never experienced severe high blood sugar, never had low blood sugar, stopped taking insulin medication at week 11, and stopped all oral diabetes medications by week 56.2 Granted, it’s only one patient. Similar results using pancreatic beta cell implants in Type 1 diabetes patients have seen success since 2000,4 but type 2 diabetes adds a layer of insulin resistance. This is a huge step for diabetes, stem cells, and science.

There were other findings that someone with diabetes may find interesting. The results2 are one page long. See you next week.

REFERENCES

1. Ruze R, Liu T, Zou X, Song J, Chen Y, Xu R, et al. Obesity and type 2 diabetes mellitus: connections in epidemiology, pathogenesis, and treatments. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2023;14:1161521.

2. Wu J, Li T, Guo M, Ji J, Meng X, Fu T, et al. Treating a type 2 diabetic patient with impaired pancreatic islet function by personalized endoderm stem cell-derived islet tissue. Cell Discov. 2024;10(1):45.

3. Labusca L, Mashayekhi K. Human adult pluripotency: Facts and questions. World J Stem Cells. 2019;11(1):1-12.

4. Shapiro AM, Lakey JR, Ryan EA, Korbutt GS, Toth E, Warnock GL, et al. Islet transplantation in seven patients with type 1 diabetes mellitus using a glucocorticoid-free immunosuppressive regimen. N Engl J Med. 2000;343(4):230-8.

Leave a comment